Peaking Lights, Gary Way, Dracula Lewis and Idiot Glee. After high school Beatty worked as a gas station janitor for four years before touring with his band »Hair Police«. His first cover design was for their first CD »Blow Out Your Blood«. Without any training or art education Beatty just sort of taught himself any technique or style which so happened to fascinate him.

I remember staring at album covers for ages as a young kid, because I understood the visual language more than the music. What was your relationship to music vs. album art like growing up?

Robert Beatty: I have definitely always been much more drawn to music if the artwork is to my liking or draws my attention. I’m much more a visual person than I am musical, so I am often guilty of judging records by their cover. I didn’t really spend much time with music as a child, no more than the normal person. I started to get into more underground music as a teenager in the mid 90’s and my interest in record covers grew from there. Records by Stereolab, Thinking Fellers Union Local 282, Cornelius, Pavement, Royal Trux, The Boredoms. The Beastie Boys’ Grand Royal magazine, which had lots of work from Mike Mills and Geoff McFetridge was also one of the things that got me really interested in design when I was a teenager.

Can you describe your design process? Do you get instructions from the bands? Or do you just get lost in the music and go for it?

Robert Beatty: It’s different for every project. I keep a sketchbook with ideas and pull lots of things from there – shapes, color palettes, compositions and text. Sometimes a band has something specific they want, but a lot of time I am given very basic guidelines and am free to go where I want with the art. I often listen to the music I am making art for while I am working.

You are also a musician. How visual is your music making process? Do you see colors and designs as you compose and play around with sounds? How does your profession as a cover designer influence your music making?

Robert Beatty: I think of music as a narrative but not with specific imagery. I like there to be movement and some sense of development even in the most abstract types of music that I make. I don’t really think of anything when I’m making music. I prefer to lose myself and let it take over. I think I am definitely more known for my art than my music now, so it is always nice when people come to find out about my music through my art. Other than that I am just glad to have time to be able to do both.

How does the creative process vary between designing your own cover and someone else’s? Which is easier for you?

Robert Beatty: It is definitely easier for me to make art for other people’s music than my own. I have so many ideas when working on art for my own music it is hard to narrow them down into something that can fit on a cover. It’s nice to have someone there to tell you what to do sometimes.

Did you ever experience a conflict between establishing a signature style and at the same time reflecting the music of your clients? It’s a difficult feat, which I reckon you’ve mastered quite successfully.

Robert Beatty: I think most people that ask me to do art for them come to me because they know my style, but I always try to fit it to each project. I don’t really think about it too much beyond that, I just do what comes naturally.

You work with the air brush technique, which can easily be associated with trash culture. How did you come about using it for your work? Why does it appeal to you?

Robert Beatty: I’ve always been a fan of airbrush art since watching Monty Python’s Flying Circus as a kid and seeing Alan Aldridge’s »Beatles Illustrated Lyrics« book. I’m a huge fan of artists like Destroy All Monsters and Jeff Keen who use »trash culture« in their work. I wish I was able to do it more successfully, but in it’s heyday airbrush art was everywhere, so it’s associated with that part of culture. I think the characteristics, the technique achieves are hard to pin down, which is part of the appeal to me. People often have no idea how I make some of the art, which I also like.

You sometimes reference past album covers. Do you have an extensive archive of album art for research purposes?

Robert Beatty:I have a pretty big collection of art books, magazines, and images that provide endless inspiration for me. I try to not directly reference anything though and try to make each piece something new. I don’t necessarily draw much from album art, I’m inspired just as much by old magazines, movies, and product packaging.

How much is your work influenced by film rather than other album art or cartoons?

Robert Beatty: Animation also provides a huge inspiration for me. I have a massive collection of obscure animation that I’ve collected over the years. I believe animation is one the most all encompassing art forms that exist and is capable of expressing so much that a painting or a piece of music cannot do on its own.

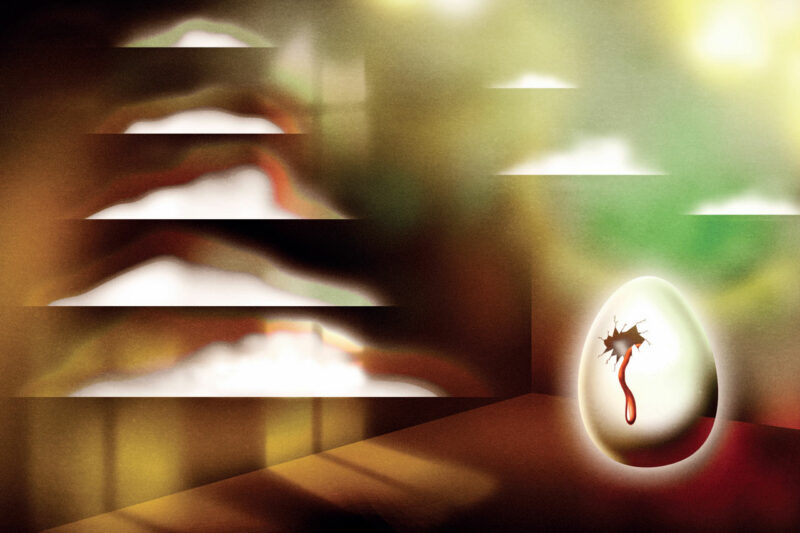

Your art work often depicts a sense of motion and transformation with an emphasis on portals or holes with things emerging. Why this repeating visual narrative?

Robert Beatty: I believe change and transformation are very important aspects of my work. I’m not necessarily trying to depict motion but the moments in between motion, which are often more interesting. I’m also interested in portraying a break from reality or something invading from somewhere else. I’ve always been drawn to that, something hiding behind or inside that is of sinister origins.