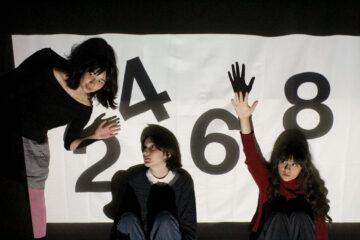

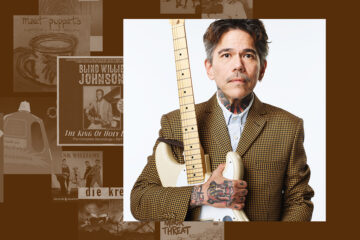

They call him a genius. A visionary. The greatest songwriter in the USA. Some compare him to Randy Newman, others to Cole Porter or Oscar Wilde. But Stephin Merritt doesn’t want to be like anybody else. He just wants to do his own thing, strum his ukulele and write about love in dingy gay bars. That’s his happy place, where the mastermind behind The Magnetic Fields is as content as a cat rubbing up against a giant cat tree. 20 years later, no one has forgotten how this brown-clad New Yorker managed to wake the pop circus from its slumber. In 1999, Stephin Merritt shot love through the heart to make it bloom again with »69 Love Songs«.

Love doesn’t know its own luck at first. In 1990s New York, Merritt stood out as a chain-smoking thirty-something songwriter with a raspy voice and lyrics that dared to be different. But in bands like Future Bible Heroes, The 6ths and The Magnetic Fields, he produced albums that sounded like Ariel Pink and the Beach Boys had been put in a gumball machine, kicked hard and the colourful pills scattered on the street. In that sense, »69 Love Songs« was a »career-defining move,« Merritt said in an interview. A step in a new direction without forgetting the past. The new album had to be different. And a little bigger. Merritt proposed 100 songs. The record company accused him of megalomania. And insisted on limiting the album to 69 songs. That way the sex reference could be marketed, the people at Merge Records thought. But the album is not about shagging. Not even about love. It is about love songs, which sounds pretty cheesy. And as an idea, it was about as creative then as it is now – not at all.

Here’s someone who doesn’t want to dwell on last week’s screwed up one-night stand, but wants to make a comprehensive statement about love songs.

Indeed, the album is different. Its sheer size, 69 bloody love songs about love songs, expresses it: Here’s someone who doesn’t want to dwell on last week’s screwed up one-night stand, but rather make a comprehensive statement about love songs, approach them as a whole, look at them from different angles and reupholster the most beautiful thing in the world, this well-worn sofa of pop history. »I like the idea of love songs in huge quantities, because it turns the idea of the love song on its head. You don’t normally see that«, says Merritt. He underlines this intention not only in his notebook, but also in the album’s musical ambitions.

Genres, styles, instruments—Merritt mixes them up like a giggling fairy godmother, touching on space rock, Irish folk and pop ballads from the eighties, only to play the sappiest ditty on the piano the next moment. In between, you can dance the night away in the disco and board across shoegaze in cowboy boots. Children’s songs juggle with adult metaphors, and yes, there’s even reggae at one point. Anything goes because nothing has to. »Punk love«, »world love«, »experimental music love«! The only genres Merritt didn’t dare to touch are rap and heavy metal – his voice is »not really suited« for it.

69 times chaos in the time it takes to smoke a cigarette

But wait a minute! Doesn’t this raise the suspicion that someone is shamelessly raiding the medicine cabinet of pop history? A sip of the delicious cough syrup from 1969 here, a few colourful pills from the eighties there—all just to throw the whole shit together on one record and boil it down again as a post-modern brew? Of course not. The musical richness of the album is a stroke of genius. Merritt leads us towards individual genres, while at the same time undermining them with exaggerated simplicity. He distorts them, makes faces at them, cuts them up. »69 Love Songs« does not lend itself to the imitation of styles. The album is as far from that as Morrissey is from reason. Instead, we see the great art of combining an appreciative and critical parody of music history. What would be the point of simply imitating styles? Nothing, you might think. But to know them and to present them through one’s own lens is the beginning of…

It is an album for all those hopefully in love and hopelessly lost.

…brilliant dilettantism. Merritt’s compares love to jazz, gin and sexy lingerie. He throws some shade at Ferdinand de Saussure, the king of signs and symbols, because apparently orchids can’t be bulldozed (»The Death of Ferdinand de Saussure«). Then there’s a synth-pop number about a super-long dog lead that isn’t really a lead at all (»Fido, Your Leash is Too Long«). Its ideas bounce off each other like pinballs in a machine. Sure, it’s all a bit tongue-in-cheek, but there’s a sincerity to it all, like that delicious fruit Cointreau. The lyrics defy easy explanations with irony and wordplay, making »69 Love Songs« a treasure trove of punchlines. It’s a whole universe that Merritt creates, filled with people, animals and whatever else pops into his head. He throws them all in and watches the crazy world unfold.

With short, sharp songs, Merritt is tailor-made for the attention span of millennials. He tells most of his stories in the time it takes to smoke a quick cigarette, and most tracks are under two minutes. If one goes over five minutes, it’s worth the wait. Where others strum their guitars for ten minutes, stare into a camp fire and rant about the American fucking dream, Merritt’s songs hit the mark like a .44 Magnum. Bang, bang, boom! It’s not that he’s a man of few words or that he’s pragmatic. Stephin Merritt just can’t stand boredom. And he tells us why. As a child, his mother often listened to the music from folk singer Judy Collins. It was a formative experience »because of the stylistic variety in her songs«—in contrast to Bob Dylan, whose »shitty records« he hated »because Dylan just sang and played guitar.

Is Stephin Merritt for real this time? Who knows? You can never be sure with him. But one thing is for sure: »69 Love Songs« is a masterpiece. It is an album for all those hopefully in love and hopelessly lost. For those who still believe in the big thing that pop music chews up like chewing gum plastered in your hair. For those who fear and fight and cry quietly and secretly because the Tinder date turned out to be a dud again. It’s an album for those who dream of this invention called love, but know that it doesn’t work the way it does in the movies. Because Merritt is many things, but he’s no fool. And so, 20 years later, he sees through a few hearts with his Camel baritone and shows what love really is: a mess. A beautiful mess.