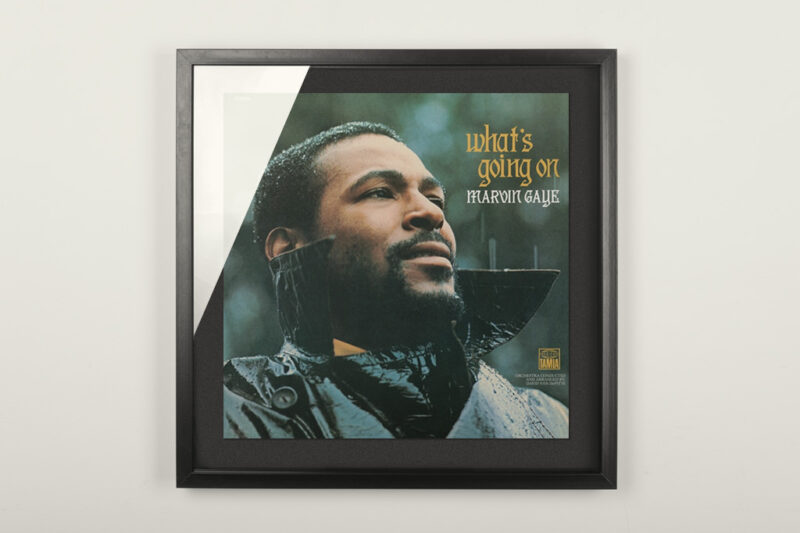

The first thought on »What’s Going On«: Is there seriously something new to say about it? A hyperclassic, one of the biggest soul albums ever and one of the most popular to date. So presumably one may expect people to be familiar with it. At least within a certain generation.

And what about younger listeners? Anyway, Rolling Stone magazine, in its 2020 edition of »The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time«, awarded Marvin Gaye’s opus magnum number one position. It is by no means certain that this position will remain unchallenged. Perhaps future rankings will see D’Angelo’s ‘Voodoo’ at the very front instead. The history of pop music still is an affair dealing with a living object of study, so shifts in time cannot be ruled out.

More important than being top spot of a list, however, is the question, whether the record is still able to elicit enthusiasm and to concern us. Cautious prognosis: It is. Because of the music, because of the lyrics, and because both still have a lot to say. Their combination naturally matches tenderness with anger and a relaxed groove with outrage.

Soul music’s first concept album

‘What’s Going On’ is regarded as soul music’s first concept album. In 1971, protests against the Vietnam War were rising, the public criticism of the government policy was growing louder. Up to that point, Marvin Gaye had been noticed for his love songs, social criticism as formulated by the likes of Sly Stone or Curtis Mayfield had not been his thing really. Now he was singing lyrics against the Vietnam War in the album’s title song, he was critical of pollution in ‘Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)’, or, in ‘Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)’, bundling social tensions and racism in the cities of the USA to form an accusation. Compared to said colleagues, Mavin Gaye’s criticism may come off as less pointed and more preachy, nevertheless, in addressing those topics he has lumped together some the big crises of his time as if magnified through a burning lens.

Da 5 Bloods

Regardless of the relative openness of the lyrics, he definitely names specific ills. For example, when Gaye sings in ‘What’s Going On’: ‘Brother, brother, brother / There’s far too many of you dying’, this does not merely mean U.S. GIs in general, but expressly the African-Americans sent to war to fight for their country, whereas being suppressed in this very country at the same time. And yet one third of the U.S. soldiers in the Vietnam War had been African-Americans, although they only formed ten percent of the U.S. population in those days. This story is told in Spike Lee’s war movie ‘Da 5 Bloods’ (2020) in which Marvin Gaye’s album comps the plot by way of musical commentary.

#BlackLivesMatter avant la lettre

Other songs have remained relevant due to the mere fact that their topics are as pressing as back then, or, see ecology, have continually worsened. »Inner City Blues« could even be considered a comment on #BlackLivesMatter avant la lettre: »Crime is increasing / Trigger happy policing / Panic is spreading / God knows where we’re heading«.

And then there is the music. Praising its merits causes a bit of writer’s block since there is plenty to read about it already. Suffice it to say perhaps that the harshness of the lyrics notwithstanding, Marvin Gaye presents himself as gentle and fragile. It is only in ‘Inner City Blues’ that he permits himself a single angry shout, very much in line with the chorus ‘Make me wanna holler’. The music keeps a stately tempo, steering clear of edges, preferring strings for emphasis. The sound, being heavy on reverberation, produces a harmonising effect, with the individual instruments stepping back, forming a many-voiced and many-rhythmic thing that never appears massive but rather slender. Still, these remarks about the sound come with reservations since the recording has a changeful history as far as mastering is concerned. (For this text, the mastering of the copy used is from the nineties (1999).)

James Jamerson on Bass

Then again, »What’s Going On« has, alongside the voice of Marvin Gaye, an instrument that ties this album together with profound singing and soft muscle. It is the bass of James Jamerson. The Motown session musician casually sketches his own melodies, plucked with such subtle beneath the surface feeling that his bass runs can spontaneously move you to tears. It is said that during the recording sessions Jamerson consumed exceptional amounts of Metaxa and played lying on his back. The question remains unanswered whether Jamerson would have summoned up the same amount of expression and elegance with less alcohol in his blood. In this case, the drugs did not do any harm, for the short term at least.