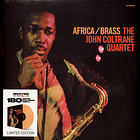

When »Africa/Brass«, the eighth album by US-saxophonist John Coltrane, came out on September 1, 1961, one of the first Impulse!-releases back then, incidentally in direct succession to Gil Evans’ »Out Of The Cool« and Oliver Nelson’s »The Blues and the Abstract Truth«, the reactions of contemporary critics are said to have been predominantly restrained. Downbeat-writer Martin Williams gave it two stars out of possible five, complaining about a lack of melodic development as well as »technical order and logic.« Sixty years later, this surprisingly reserved assessment may be regarded as largely revised. Nevertheless, it should be noted that »Africa/Brass« in general perception, especially in comparison with albums such as „Giant Steps” (1960), »My Favorite Things« (1961), »Olé« (1961) or »A Love Supreme« (1965), which form the temporal environment of its creation, tends to be somewhat overshadowed by these classics recognized as timeless masterpieces.

One reason for this may be that »Africa/Brass« must be considered an »atypical« Coltrane album in at least one respect: The John Coltrane Quartet, the performer attribution on the original cover, only partially corresponds to the true conditions during the recording sessions. A total of 18 musicians were involved in the sessions of May 23 and June 7, 1961 in the Van Gelder Studios in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, which had been opened two years earlier – and the quartet was actually a quintet in this intermediate phase, since Coltrane had temporarily engaged Art Davis in addition to Reggie Workman. Not as an alternative, but as a second bass player, mind you: a decidedly unusual line-up with which Coltrane intended to integrate ensemble constellations of certain African recordings into his work. The idea of actively using casting questions as a momentum and creative factor, of making them decisive adjusting screws in the production of jazz, in order to tap and release otherwise unattainable energy potentials from the combination of specific musical personalities, was probably first encountered by Coltrane as a member of the Miles Davis Quintet. Even more important than what was being played became who was playing it with whom.

In those years of epochal change from the end of the fifties to the beginning of the sixties, hardly anyone knew better than Creed Taylor about the virtuoso play with the kairos of the recording session. In 1960, he was commissioned by ABC-Paramount to launch Impulse!, a sub-label specializing in jazz, before leaving shortly thereafter for Verve to help shape the face of the bossa nova and later, with CTI, to become a style-setter for soul jazz. With the exclusive signing of John Coltrane, Taylor succeeded in securing long-term business ties with the most famous jazz musician of the time, alongside Miles Davis, to Impulse! – a connection that would subsequently prove to be immensely fruitful for Coltrane artistically and to which he would remain loyal until his death in 1967.

Only in retrospect does it come to light that this production might have been Coltrane’s most ambitious undertaking: the high art of improvised rhapsodic form, unfolded in all spatiotemporal dimensions.

In this respect, »Africa/Brass« definitely marks a beginning. At the same time, it documents a phase of transition: The period around 1960 shows Coltrane in search of a working band. Already in Eddie Vinson’s band, at the very beginning of his career, the musician, born in North Carolina in 1926, switched from alto to tenor saxophone. However, he retained the alto intonation on the lower-pitched instrument, which gave him his very own, characteristically bright and haunting tone. From 1957 on, Coltrane increasingly pursued the project of emancipating and dissolving harmonic structures in his playing. Starting with chord breaks, he developed a rhythmically condensed style whose single-note chains seem to spread out rather horizontally – the contemporary jazz critic Ira Gitler coined the word »sheets of sound« in connection with Coltrane’s innovative style of playing. In moments of highest intensity, these modal scales, dating back to his collaboration with Davis and Monk, culminated in archaic-universal sound events – pre-linguistic phonograms of pure expression, eruptive immediacy, if you will.

In addition, the renunciation of chord patterns and progressions opens up the music: It becomes ambiguous in real time because it often remains unclear which key is currently being played. A close agreement between the soloist and pianist is essential at this point. This intimate partner had already been found with McCoy Tyner at the time of the recordings for »Africa/Brass« as was drummer Elvin Jones, whose polyrhythmic networks were to have a decisive influence on the sound aesthetics of the Coltrane Quartet. But the quartet’s classic line-up with Jimmy Garrison on bass, which would remain stable for more than half a decade, wasn’t complete until the fall of 1961. In this situation, Coltrane decides on »Africa/Brass« to expand the quartet, which was in a sense still fluid and not completely hardened, into a big band in places. Not least the arrangements of Eric Dolphy, who can also be heard on »Africa“ and »Blues Minor«, as well as McCoy Tyner, with the use of rarer wind instruments in jazz such as French horn or euphonium on Gil Evans leaning executed by virtuosos like trumpeters Freddie Hubbard and Booker Little, are responsible for the fact that »Africa/Brass« is perceived as the »somewhat different« Coltrane record.

Thematically, »Africa/Brass« also operates at the intersection of several poles, looking back and forward in a Janus-faced manner: With the 17 African states that had newly appeared on the world map in 1960 alone, the view goes into the future; with reminiscences of the time of slavery and the experience of diaspora into the past. In the 16 minutes and 28 seconds of »Africa«, the rhythmic dialogue of the two bassists creates a hypnotic maelstrom over which the soloists, Tyner and Jones in addition to Coltrane, spread their powerful lyrical wings, soaring above the sun-scorched land repeatedly scoured by iridescent timbres. Both in terms of musical expression of heat and in terms of repetitive structure, the parallels to »Olé«, recorded only two days later, on June 25, 1961, are unmistakable. With »Greensleeves« Coltrane proceeds analogously to his interpretation of the Rodgers/Hammerstein standard »My Favorite Things«: the soprano saxophone takes center stage as the lead voice, the theme of the traditional becomes the starting point of modal, epic-ecstatic de- and reconstruction. In turn, »Blues Minor«, the third and last track on »Africa/Brass«, seems almost like a recourse to the hard bop of the Prestige years.

Only in retrospect does it come to light that this production might have been Coltrane’s most ambitious undertaking: the high art of improvised rhapsodic form, unfolded in all spatiotemporal dimensions. Later editions made available additional takes of »Africa« and »Greensleeves« alongside »Song of the Underground Railroad” and »The Damned Don’t Cry« recorded at the May 23, 1961 session. The various inspirations that emanated from this album can be seen in its reception history: Roger McGuinn stated that The Byrds bent over it when it came to recording »Eight Miles High«; minimal music mastermind Steve Reich was also impressed: »basically half an hour in E«.