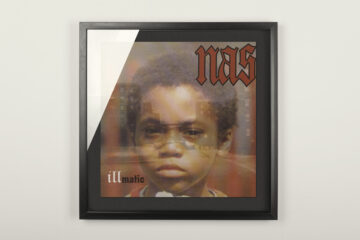

Are art and business compatible? When does success become betrayal? And do jazz snobs really exist? Few records have raised these questions more forcefully than Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters. Released in October 1973, it reached gold status within six months and later became the first jazz record ever to go platinum. This was despite Columbia Records allegedly predicting poor sales prospects: the four tracks appealed to neither the record company’s R&B nor jazz fans.

Head Hunters

»Only the promo guy for college kids liked it,« Herbie Hancock quotes producer David Rubinson in his autobiography Possibilities (2014). Almost as well known as the album itself is the criticism of it. For the journalist Lee Underwood, the music was »schizoid« and »commercial rubbish«, while the conservative critic Stanley Crouch saw the jazz pianist at the »crossroads« of his own demise. Did this mark the final sell-out of jazz to the mainstream?

»Jazz also stood for the absence of ownership.«

Although the era of fusion had long since dawned, Hancock’s bubbling firecracker of jazz funk remains one of the most famous taboo-breakers in music history. Even the opening track, »Chameleon« (which has since become an original nickname for its composer), with its catchy, unmistakably meowing synths, lies outside the tradition of what defined jazz in its origins and what can be described as the African-American experience.

As the author Diedrich Diederichsen writes, this includes the spontaneous, skilful and ephemeral use of sounds as if they were merely borrowed: jazz also stood for the absence of ownership. This allowed him to draw his power from the moment, from the impossibility, or at least the improbability, of being reduced to an assembly-line reproduction. The fact that Headhunters, the specially formed band, was no longer meant to improvise during stage performances all of a sudden, but simply play the tracks from the album with as few changes as possible, ran contrary to this idea.

Making music theft-proof

50 years on, the scandal can be unravelled in a number of ways. To begin with, Hancock’s musical journey began early, mainly through his collaboration with Miles Davis in his second quintet, who listened to the Rolling Stones, Cream and Jimi Hendrix in the sixties. »If Miles thought something was great, I would listen to it,« Hancock told Christian Broecking in a 2007 interview. »And sometimes I got the impression that some things were blown out of proportion, especially the connection between jazz and racism. (…) Jazz is about reaching out to other cultures and genres, opening up and combining the different influences into new sounds. That is the history of jazz as I know it.«

»The fear of being robbed of their own music by white capitalism was therefore justifiably large. Only that, in order to defend themselves, they used capitalist and racist systems of signs for themselves.«

Hancock’s critics were bothered by this attitude, and »Head Hunters« set the ball rolling on this kind of criticism. Some of them had previously been socialised by the race records, a form of labelling that primarily ensured the segregation and exploitation of Afro-American musicians. The fear of being robbed of their own music by white capitalism was therefore justifiably large. Only that, in order to defend themselves, they used capitalist and racist systems of signs for themselves. Bebop, swing and conceptual utopias like that of the only true jazz were like seals of authenticity on products that were supposed to thrive, but only as long as they were played by certain musicians and brought success to certain labels. To put it bluntly, people were afraid of “their own” jazz being stolen from them.

A few decades later, with the Internet and all its excesses, jazz would face a much bigger opponent. Its identity as a fleeting art form to be preserved is forced to confront new conditions in which the momentary, the ephemeral, the original and niche art have a particularly hard time. Seen in this light, »Head Hunters«, one of the most famous fusion records of all time, stands more than anything else for an organic evolution of jazz that ensured its survival in the long term.