What Eddie Hazel elicits from his instrument in »Maggot Brain«, the song that opens the third album of the same name by George Clinton’s more or less parallel to his Paliament formation running band Funkadelic, is far more than a guitar solo. For ten and a half minutes, Hazel works directly on the neural pathways of listener’s brains, playing – quite in the footsteps of Jimi Hendrix – less on the strings of his electric guitar than on the electronics themselves: a blues-infused trip into the innermost regions under the skullcap, a psychedelic excursion into the land of teeming, melting thought. In a sonorous voice transposed downwards, Clinton intones beforehand: »Mother Earth is pregnant for the third time / For y’all have knocked her up / I have tasted the maggots in the mind of the universe / I was not offended / For I knew I had to rise above it all / Or drown in my own shit«. Legend has it that his guitarist was instructed to play the first half of his part as if his mother had just died, and the second as if she were still among the living.

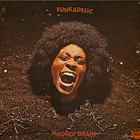

»Wars of Armageddon«, the almost equally epic conclusion to the longplayer released 50 years ago – on 12th of July in 1971 to be precise – on Westbound Records, is a surrealistic sound collage of baby cries, street noises, cuckoo clocks and slogans of the black civil rights movement taken to the absurd (»More power to the people / More pussy to the power / More pussy to the people / More power to the pussy / More pussy to the power«), transported by a rudimentary funk riff ostinato and ending in a distant detonation that turns into the pulse of a heartbeat. Here, with the expressive, outwardly turned counterpart to the introspection of »Maggot Brain«, the circle closes: one listens to the heartbeats of the foetus with which Mother Earth is pregnant. The cycle of becoming and passing away is also illustrated by the iconic, disturbing cover: Joel Brodsky’s photo shows the head of Barbara Cheeseborough, the black model whose likeness graced the first issue of the African-American women’s magazine Essence in 1970 and who thus became the trendsetter of an Afrocentric ideal of beauty, stuck up to her neck in the mud. Her eyes closed, a cry seems to escape her mouth. Maggots are nowhere to be seen, but can be guessed at everywhere: in her afro, in the soil surrounding her. On the back, only a bony skull remains of her countenance. Fittingly, the artwork quotes an excerpt from a manifesto of the satanic Process Church of the Final Judgement on the concept of fear.

Far more than on his two predecessors, Clinton goes in search of the dark side of funk with »Maggot Brain«, interspersing the pleasure principle usually triumphant in it with dystopian, apocalyptic eschatology, juxtaposing the celebration of life with an oppressive doomsday mood.

The five songs, that are found in between and make up pretty much the other half of the album in terms of time, stand in strange contrast to the bracket enclosing them, seeming at first irritatingly conventional in comparison to this sonic fiction overload. „Can You Get to That”, a country-blues remake of the Parliament single »What You Been Growing«, features Isaac Hayes’ backing choir Hot Buttered Soul with singers Pat Lewis, Dianne Lewis and Rose Williams – there is also a reminiscence of the fact that Clinton’s roots are in doo-wop resonating in it. »Hit It and Quit It« is a soul number with a gospel feel, in which Bernie Worrell sets luscious accents both behind the microphone and on keyboards. »You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks«, at the time the first, not particularly successful single release and today the most sampled track on »Maggot Brain«, is sung by Billy Nelson, whose detuned basslines counteract the impression of a Sly & the Family Stone anthem. With »Super Stupid«, on the other hand, Funkadelic celebrate monolithic, electrified blues rock in the sense of the Band of Gypsys, Hazel here also on the mic in the Hendrix position. The antithesis follows immediately: the exaggerated stereo effects in »Back In Our Minds« already signal that this assertion is not to be believed. The fact that Ramon ‘Tiki’ Fulwood, who was later poached by Miles Davis, sits on drums here, lends an indestructible rhythmic signature even to pieces that are not entirely convincing. It is above all the groove, as multifaceted as it may be, that breathes coherence into this Janus-faced funk-rock hybrid.

Far more than on his two predecessors, the self-titled debut and »Free Your Mind And Your Ass Will Follow«, Clinton goes in search of the dark side of funk with »Maggot Brain«, interspersing the pleasure principle usually triumphant in it with dystopian, apocalyptic eschatology, juxtaposing the celebration of life with an oppressive doomsday mood. LSD experience, Vietnam trauma and the impoverishment of the black population in the segregated neighbourhoods of North American cities marked by the decline of the automobile industry, especially in Detroit, the home of Funkadelic, converge in »Maggot Brain« to form a harrowing statement about the condition of mankind on its way from a dark present to an even darker future – monument and memorial in equal measure. Less than dialectics, Clinton is more concerned with interstices, transitions, transformation and metamorphosis here. Against the backdrop of the threat posed by a weapon that has the potential to depict people as grease films on the rubble of their cities (a theme that will become even more central to Funkadelic in the course of the seventies), the later inventor of P-Funk reacts here, at the height of Funkadelic’s first phase, with a fusion of affirmation and deconstruction, combined with a multiple, ambiguous over-coding of blackness. An experience that even today, 50 years later, hardly any listener is able to escape.