Berlin is the »jazz capital«, the »jazz metropolis« or the »jazz mecca«—in any case, there is a lot to feel and hear in the capital, especially the words: »You can actually hear jazz here every day«. And it’s true, Berlin has the Jazzfest, the Jazzwoche, XJAZZ! and Rejazz, a dozen other festivals in allotment gardens and hidden corners, and everywhere else where the sound that once drew a critical frown from the weekly newspapers can be heard: the jazz clubs.

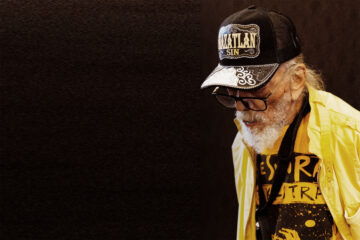

Entangled Grounds - The Sound Of Xjazz! Berlin

Jazz In Der Kammer Nr.71

There are so many of them in Berlin that counting them would take you to the anatomical limits of your fingers. From A-Trane to Zig Zag, the framed ballast of the last century hangs on the walls. On stage, people try to escape from it via their playing. At Klunkerkranich you can sweat out the jazz basement vibe over the rooftops, at Fluxbau you can gaze optimistically across the Spree towards the Alex, and at Donau 115 you can soak up the avant-garde between the old floor lamps. Berlin is a city where anything goes. It’s a promise that’s still good enough, and it’s one of the reasons why so many people are drawn to the city.

Go to Berlin, young man

Or be drawn there. Petter Eldh is the kind of musician whom programmes like to cunningly introduce by writing that there is no need to introduce him. In other words, Eldh, born in Gothenburg, is a »fixed star in the firmament«. He arrived in Berlin for the first time in 2006. To party and buy some hip-hop records in the backyard of HHV as it was back then. He spent a few more years in Berlin—paying rent. Today Eldh says: »I grew up with beats and sample culture, but neglected this side of my life during my double bass studies—until the city opened it up again«.

The bassist now leads a variety of projects, one of which is called Post Koma and sounds like J Dilla has returned in the guise of a jazz conductor after a two-decade sabbatical. Eldh, of course, has an MPC alongside modular bling-bling and a synthesiser museum in his studio. »The city was my new beginning back then, I would wander around for days, stumble into all these little clubs and simply join in. It was all about free improvisation. It’s very different now, and I’m happy about that. My interests have changed because of the city, my perspectives in it as well.«

»Some people can play progressive music without thinking progressively.«

Petter Eldh

Improvisation was the Berlin School back then. Free, open and avant-garde—that’s what jazz has stood for in Berlin ever since Peter Brötzmann coughed through his saxophone for the first time in the sixties. And yes, this principle still exists as a long outdated tradition. »Or outdated for me,« Eldh corrects himself. »Some people can play progressive music without thinking progressively. That doesn’t encourage meeting new people.«

And he’s not alone in thinking like that. A lot of people think that, especially the young. Berlin is moving away from the non-academic punk spirit of blathering and strumming—although Eldh says it’s still a form of expression that’s appreciated. Nowadays, both the mind and the music seems to have arrived in the right century. This includes technical training as well as a manner of thinking that is not stuck in the yesteryear.

One of those who is thinking ahead is Otis Sandsjö, Eldh’s mate from Gothenburg and his saxophone colleague in Y-Otis. A band that can be seen playing at the most important contemporary jazz festivals, because they jazz it! Sandsjö moved to Berlin in his early 20s, finished his studies and was open to the adventure of living in a city that had previously offered him only extended summer holidays. »All I knew was that there was an international community here, improvisation was happening everywhere, everything was DIY and people were even booking tours for themselves to play their crazy music.«

Between the Dream and German bureaucracy

A few years have passed since then, and Sandsjö has added a family life to his musical one. »Nevertheless, the city still has a mystical aura for me. Berlin is more of a dream than anything else, probably because people here always have dreams and create an energy that you can’t find anywhere else.« But over time, reality begins to mix with the dream, says Sandsjö. »At some point you realise that Berlin is just another German city with German bureaucracy.«

But the dream remains omnipresent in the city, says Sandsjö. »Young people still move to Berlin. They may not have the same dream we had when we chose this city, they may even have a completely different one in their heads—one that is just as incompatible with reality as ours was back then. But they will do everything they can to live their dream. That’s what has always made this city so special, hasn’t it?«

Eldh adds that you shouldn’t forget that everything is built on something—what people do here has a history, in fact it always needs a history, because other people have built something before, on which »we, and what we simply call the scene«, can continue to build. »That’s nice, but also dangerous,« Sandsjö interjects. »Because the idea of a legacy is inscribed in this process of creating and continuing to create, and that can also be conservative, especially if it dissolves this young, dreamy vibe.«

»The idea of a legacy is inscribed in the process of creating and continuing to create, and this can also be conservative«.

Otis Sandsjö

The vibe may be a dream, but it feels very real for many people. There are reasons for this. Even if rents continue to rise, rehearsal rooms are being replaced by car parks and the planned House of Jazz is being axed: Berlin is still what red-rose politicians call »affordable« compared to London or Paris. And although the Senate is cutting back on the independent scene, it continues to pour money »into culture«.

The question is: for how long? The independent scene will be the main target of cuts in the cultural budget for the coming years. While the Senator for Culture did not want to promote »high culture and commercial culture alone«, some are now talking of »complete eradication« and »scorched earth«. After all, the cuts will affect those artists who have no jobs, no rehearsal space and modest working conditions: in other words, the precariat.

Conditions like in the UK?

This can be judged from a number of perspectives, including from the outside: »The way Berlin looks after art and artists is much more considerate than in the UK,« says Cassie Kinoshi, for instance. The British musician is part of the young, new jazz generation in London: That is to say She was part of it. Kinoshi has been living in Berlin for a few months now and says: »Jazz is combined with classical music here. Also, the German mentality, with its work-life balance, appeals to me much more than the one in London.«

»If you want to be successful there, you have to adapt.«

Cassie Kinoshi

Furthermore, there are no prominent jazz figures in Berlin as Kinoshi can objectively state from the outside. In London, jazz is represented by a select few at the top, yet there is a much more complex scene than is commonly portrayed. This results in a narrow-minded approach to new ideas and perspectives, as the limited number of names give the impression that there is a distinctive sound associated with London.

»In Berlin, on the other hand, I breathe a sigh of relief because there is still room here for small communities of improvising musicians who are tied to a particular place, rather than to a city as a whole.« Kinoshi emphasises the importance of the availability of spaces for experimentation. They exist in London as well, of course, she says. The crucial distinction is that the drained funding culture intensifies the concept of competition to the point of self-destruction. If you want to succeed there, you inevitably have to adapt.

Kinoshi may not have had any experience of Berlin’s funding culture, and she comes to the city as a well-known artist. Nevertheless, her view reflects a possible future: If politicians support »high and commercial culture alone«, British conditions will soon prevail in Berlin. There, subsidies are cut less often but more often cut altogether. This affects clubs, artists and culture that take place elsewhere than in the opera houses or on the radio.

In search of luxury goods

A plea for the niche is therefore made by those who look at Berlin from the inside. One of them is Tilo Weber. He is in his mid-30s and one of the city’s most sought-after drummers.

The prerequisite for his stylistic range between vocal ensemble and pop group expansion is, of course, having the space and time to experiment and fail. After all, the main driving force in jazz should never be the exploitation of the result. It should be about finding a way to get a result. »It’s exhausting, it can lead to stress and a few panic attacks, but it’s my approach. And many young people in this city share it.«

Weber studied at the Berlin Jazz Institute with John Hollenbeck in his twenties, is the drummer for David Friedman and won the German Jazz Award in 2022. And he has arrived in Berlin. But he doesn’t want to sugarcoat anything. Time and space are increasingly becoming luxury goods. That’s why the venues need to be preserved at the very least. »When I first came here, I played at the A-Trane and other traditional clubs a lot. But when I go to a pub like the Donau, where the young people from Neukölln hang out all the time, drinking beer and listening to avant-garde stuff, it has a different vibe.«

A vibe that ACT pianist Johanna Summer also wanted to find. Born in ’95, Summer came to the city after completing her undergraduate studies and wanted to see what it was like working as a freelance musician; she succeeded: »My approach to improvising on classical piano works and playing solo piano in general has crystallised here,« says Summer. She has since resurrected Robert Schumann on two albums and found her »very own sound«, as Igor Levit puts it. And she performs in concert halls all over Europe.

Related reviews

But Sommer still prefers to live in Dresden. She speaks of Berlin as a laboratory for self-study. It is everything, but that’s why it’s also so exhausting, overwhelming, a lot. It was different in Cologne, where she lived in between. »There you would get the message much quicker if someone new came to town and made cool music—simply because there aren’t that many opportunities and everyone plays with everyone else,« says Summer.

Having said that, Berlin is still the place to be if you want to play lots of sessions, go to gigs every night and take in the wholes scene. She goes there herself at least once a month. To the Pierre-Boulez-Saal, or the Donau when the programme is right and also to the A-Trane. »You can catch some great jazz in Berlin every night of the week.« As long as there’s room for it, all is well. Because where jazz is played, the music also changes. That is the nature of the genre. The rest is just politics.