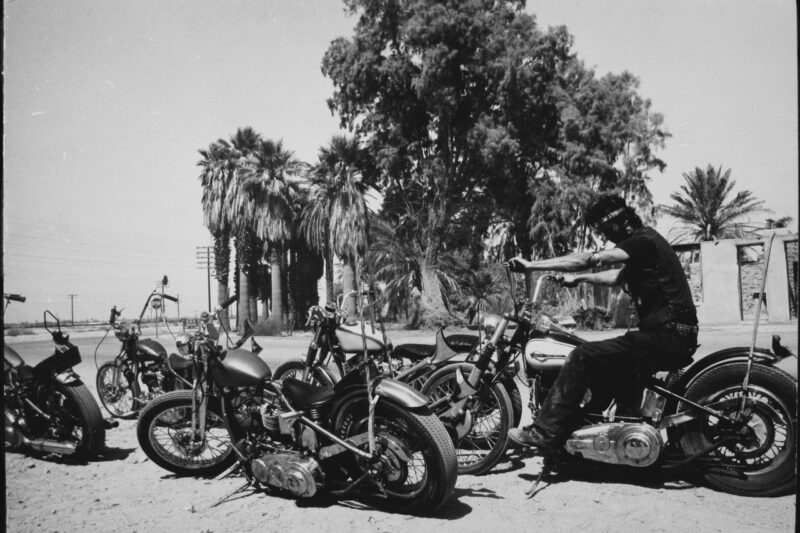

The black and white photographs mounted on cardboard show sign of wear conjuring images of a younger Hopper leafing through his impressive library of abstract impressions over and over again as he prepares for his first photography exhibition at Fort Worth Art Center Museum, Texas in 1969. It would be a tough piece of work to edit this collection as, just like scenes of a movie, each photograph is part of a larger narrative: political photos of a Martin Luther King speech, a sequence of voyeuristic shots depicting a homeless guy in a trench coat, face hidden by a large brimmed hat packing his material existence into a tattered suitcase, hippies at a ‘love-in’ and portraits of America’s new artistic elite unite to create a bigger picture. A bigger picture of an increasingly contradictory post-WW2 America, an America fighting to break out of white picket fenced barriers, an America united not by patriotism but by the dawning dystopia that once was the American dream.

Hopper’s directorial debut Easy Rider (1969), in which he also acted, rebelled against the frigid expectations of Hollywood yet was highly acclaimed among the film world elite. He had the cultural finesse to link the mainstream with the avant-garde and it is this character who makes these photographs stand out. A thirsty character seeking vital moments driven by curiosity and a child-like lack of shame. His series of Hell’s Angel bikers photographed without any sense of fear make him the photographic equivalent of Hunter S. Thompson’s gonzo journalism. His subjects aren’t exposed to judgement, he doesn’t build a wall between him and them and he doesn’t draw any conclusions – this is the viewers job.