Altın Gün, Derya Yıldırım & Grup Şimşek or Gaye Su Akyol are usually mentioned in the same breath, even though the stylistic overlap between these bands and musicians is considerably small. This can be explained by their references to Anatolian folk music or the sound of the so-called Anadolu Pop, which formed in Turkey in the 1960s. Bağlama sounds, odd time signatures and Turkish lyrics in the tradition of the Aşıks, traveling folk singers, were fused with rock music and psychedelic echoes by groups and singers such as Selda, Barış Manço, Erkin Koray, Ersen or Moğollar to create a new sound aesthetic. While nowadays heaps of seminal records are being reissued, producers from Barış K to Grup Ses pick up on it as well and revive it in a dance or hip-hop context. Does that mean that we are facing a full-on revival?

It may seem that way at first. However, these new and sometimes quite different approaches were already preceded in mid-1990s by bands such as Replikas or Zen and their successor, the still highly active outfit Baba Zula. The new interpretations and reissues are also accompanied by a series of compilations which, like »Saz Power« and »The New Generation Of Turkish Psychedelic Volume I,« cast a spotlight on contemporary approaches, while »Songs Of Gastarbeiter Vol. 1« documented the history of Anatolian music in the old FRG, re-presenting old music as much as highlighting historical continuities. The latter of these compilations puts a focus on an important and mostly overlooked turn in the history of Anadolu Pop, which in Turkey reached its nadir in the eighties and early nineties and was barely kept alive by big stars like Barış Manço and Ersen, but thrived in West Germany. Anadolu Pop lived on elsewhere. Also Yıldırım is certain: if the new interest for Anatolian music constitutes hype, then it’s one that has actually never faded away. »Just because some hipster from Neukölln is now listening to Altın Gün doesn’t mean it’s becoming fashionable now. It’s always been there,« says the Hamburg-born artist.

Nevertheless, the renewed attention to Anatolian music in general and Anadolu Pop in particular provides an occasion for an urgently needed reappraisal of its history. No matter how many reissues and compilations are published: a lot of patchwork alone doesn’t paint a holistic picture. »We lost so many things that are fading away, because it was not written, there is nothing. More and more, people are not interested in listening to folkloric music,« says Ergin Bener, an important figure in the Turkish music industry in the 1960s and 1970s, to the British journalist Daniel Spicer in his book »The Turkish Music Explosion: Anadolu Psych 1965 -1980«. And although the renewed interest for Anadolu Pop may indicate that Bener is at least partially wrong, there remain a lot of unanswered questions and unexplored side aspects of its history such as the story of the Afro-Turkish singer Esmeray, which are only slowly being explored.

»Just because some hipster from Neukölln is now listening to Altın Gün doesn’t mean it’s becoming fashionable now. It’s always been there.«

Derya Yildirim

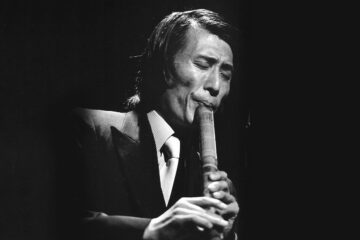

So how was this music created, and under what circumstances? Anyone who wants to understand the story of Anadolu Pop from its beginnings in the late 1950s and early 1960s to today has to start even further in the past. With the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, a rigid process of modernisation was intensified under the rule of Kemal Atatürk. It was not limited to political issues but also had decisive cultural ramifications. The ideological impulses came from the sociologist Ziya Gökalp, who in his »The Principles of Turkism« formulated the idea of »a nation […] made up of individuals who share a common language, religion, morality, and aesthetics, that is to say, who have received the same education.« Thus, Gökalp suggested a break with classical Turkish music and instead pleaded for a return to pre-Islamic forms of music and especially folk music. Government support for the practice of centuries-old musical traditions laid one of the first cornerstones for the later emergence of Anadolu Pop: more attention was drawn to instruments such as the saz and ney as well as to classic folk songs, the türküler.

Although the nationalist state largely resisted external influences from especially the Arab world by for example banning Arabic music from the radio between the 1930s and 1940s, American musical styles and dances such as rock’n’roll and the twist fell on fertile ground in 1950s Turkey. Inspired by the music and films of Elvis Presley or Bill Haley and instrumental records by the Shadows and the Ventures, the Anadolu pop pioneer Erkin Koray played a concert in December 1957 that went down in the annals as one of the first rock’n’roll gigs in Turkish history, while another star of the soon-to-be-born scene had his epiphany amidst the audience: Barış Manço. This new generation of Turkish musicians oriented towards what was happening all over world and especially in Europe. »All the famous ones – Barış Manço, Cem Karaca, Erkin Koray – attended language schools,« says Ercan Demirel, who runs the Ironhand label together with Cem Şeftalicioğlu and is a tireless archivist of Turkish and Turkish-German music history. The aspirations of the young musicians thus reflected that of the state in which they grew up. »As a large country, they wanted to have a connection to Europe.«_

Musicians such as Koray, Manço, Erol Büyükburç and Arif Sağ began to release their first records at the start of the 1960s. The palette ranged from cover versions of popular rock songs to chanson and yé-yé pieces in their respective original languages, but Anatolian songs, Turkish lyrics and the corresponding instruments became increasingly important, too. »Cem Karaca heard the bağlama for the first time during his military service. It touched him deeply, he had just married and was in love«, says Demirel about another of the key figures in the genre, who soon went on to make the instrument play a central role in his music. Parallel to these first scattered activities, institutional support for the new musical synthesis was forming. After Tülay German had already pre-defined the rapprochement between folk music and rock at the core of Anadolu Pop at the Balkan Melodies Festival in 1964 with a modern version of the traditional »Burçak Tarlası,« Altın Microphone, a competition organised by the newspaper Hürriyet, first took place in the following year. Its guidelines explicitly required the musicians to write songs with Turkish lyrics or to rearrange traditional material and thus gave them all the more the opportunity to solidify the timid beginnings of a new genre. It was a crucial moment in the country’s music history that was also accompanied by the establishment of a label on which among others Silûetler, Ali Atasagun, Cem Karaca & Apaşlar, and Moğollar released singles.

You can find the Vinyl records about Anadolu Pop in the [Webshop of HHV Records](https://www.hhv.de/shop/en/anadolu-pop/i:D2N4S0SP15678.)

It was however the Sayan label, launched in 1964, that soon became the most important platform for the new sound of this thriving generation. Moğollar, founded in 1967, made a name for themselves there with a psychedelic sound and over the following years became both a melting pot and a catalyst of the genre whose name was coined by their co-founder Murat Ses in regards to his band: Anadolu Pop. Ersen, Manço, Selda and Karaca worked together with the group at different times before it disbanded in 1976 after many line-up changes. After the globally tumultuous year of 1968, other bands came together and pursued their own visions of Anadolu Pop, while Moğollar evolved further, integrating more and more Anatolian elements into their music. Within a few years, a wide range of releases by for example Kardaşlar with Seyhan Karabay, who was also active as a solo artist, and Karaca, or Apaşlar, in which the two of them worked together with the German Ferdy Klein Orchestra, were released. Anadolu Pop flourished also as a countercultural phenomenon like in the case of the short-lived band Bunalım, who drew attention to themselves with wild psych-rock and »L! S! D!« shouts. The genre, however, also became more nuanced and experimental – electronic elements found their way into it, while albums such as Erkin Koray’s »Electronik Türküler« eschewed conventional songwriting. Regardless, Anadolu Pop also became a bestseller: 3-Hür-El, literally a band of brothers, rose to become one of the most commercially successful Turkish bands of the early 1970s.

It was 3-Hür-El who – however seriously – proclaimed the death of Anadolu Rock in 1975. Prematurely perhaps, but the cocky statement proved to be clairvoyant just a few years later: although Barış Manço with his Kurtalan Ekspres made it clear with their LP »2023,« released the same year, that they were looking forward to an even more exciting future, and artists like Edip Akbayram and Dostlar picked up steam in the mid-1970s, from 1980 onwards only a few Anadolu Pop albums were released besides the ones by established stars of the genre like Manço or Ersen. The reasons for that are complex. Demirel emphasises that a younger generation had lost interest in the sound and that some of the most important characters, such as Koray and Karaca, had left the country for various reasons, while Fikret Kızılok settled down after the release of his curious debut album »Not Defterimden« – an atmospherically dense spoken word record inspired by the electronic avant-garde – returned to his day job and practiced as a dentist.

However, the late 1970s in Turkey were also marked by a worsening political climate. Economic crises, constantly changing governments, the increasing oppression of the Kurdish sections of the population and, last but not least, the open violent disputes between fascist and communist groups did not leave the music world unaffected. The growing violence was reason enough for Karaca to leave the country. The military coup in September 1980 was followed by a three-year phase marked by waves of arrests and repressions. The protest singer and left-wing activist Selda Bağcan for example served three sentences between 1981 and 1984 for her political commitment. »From then on, things are going downhill in Turkey culturally«, says Sebastian Reier, also known by his DJ pseudonym Booty Carrell. »Of course the music couldn’t be killed and there was fantastic music even after 1980, but a lot of it was actually recorded in Germany.« There, the 1980s were shaped by groups such as the disco-folk duo Derdiyoklar İkilisi and Karaca, who published his German-language album »Die Kanaken« during his extended stay in the country, while a star like Erkin Koray partially recorded albums such as 1982’s »Benden Sana« in Germany.

»In essence, I think it’s about the fact that music in the 1960s and 1907s presented us with visions of living together that have not yet materialised. That’s why I think it remains totally up-to-date.«

Booty Carrell

In Turkey, however, the legacy of Anadolu Pop was not taken up again until the early and mid-1990s. In addition to reunions of groups such as Moğollar and 3-Hür-El at the beginning of the decade, it was Haluk Levent whose interpretation of classic material was greeted with open arms – despite them being carbon copies of a once futuristic concept. »He took folk songs and re-recorded them as hard rock versions with exactly the same arrangements,« Demirel says. »Then came bands like Replikas or Fairuz Derin Bulut – whose guitarist now lives in Cologne and performs under the name Elektro Hafiz – who conveyed the taste of Anatolia, but sounded different from Barış Manço and others.« Also the collective Zen, the predecessor of Baba Zulu, were and still are key players and together with bands as diverse as maNga, Ayyuka, Konstrukt or iNSANLAR pushed the envelope by translating tried and tested into a contemporary argot. Thus, also Derya Yıldırım & Grup Şimşek or Gaye Su Akyol do not necessarily represent a renewal of a sound that was believed to be forgotten, but rather represent its logical and seamless evolution. Altın Gün however is best understood as a retro band that largely draws on an existing repertoire. »They use exactly the same musical language«, confirms Volga Çoban from the reissue label Arşivplak, while Demirel compares their approach to that of Haluk Levent.

Yıldırım, who with her music orients herself more towards poetry and forms of folk music than Anadolu Pop, doesn’t mind being compared to these other and sometimes very different groups: »I actually think it’s nice when others put us in the same category. As long as it stays open!« Openness is also the keyword that characterises this new generation: both Altın Gün and Yıldırım & Grup Şimşek are international bands that have the potential to break away from fixed constructs of identity. Just as perhaps the renewed interest in Anadolu Pop can be explained by the fact that it came with the promise of a more international and open world. »In essence, I think it’s about the fact that music in the 1960s and 1907s presented us with visions of living together that have not yet materialised,« says Reier. »That’s why I think it remains totally up-to-date.« And Yıldırım even goes as far as ascribing timelessness to one of the elements of this sound: »Anatolian folk music has something that is being understood all over the world.« It’s not so much of a full-on revival then, but rather a late realisation.

You can find the Vinyl records about Anadolu Pop in the [Webshop of HHV Records](https://www.hhv.de/shop/en/anadolu-pop/i:D2N4S0SP15678.)