Uprisings, men wielding flame throwers, the words »inferiority complex«. Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Bob Marley. Closed gates in front of luxury condos. The cover of Oluko Imo’s last album is as chaotic as decolonization itself. The sole anchor is provided by the musician, who’s looking ahead. His name is highlighted by the colors of pan-Africanism. Confronted with the complications of History, Oloku Imo never left a doubt as to where he stood.

Imo was raised in the slums of Port-of-Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago. After the country gained independence from British rule in 1962, President Williams promised political self-determination. Instead, he led corporations into the young Caribbean state. Discontent grew in the slums. In 1970, it erupted in an insurrection. After a few months (and mutinies within the army), the state managed to suppress the riots. Yet, two of its moments had irreversibly shaped Imo’s thinking.

First, the revolt had made it clear that national independency was but the beginning of decolonization. An overhaul of thinking was necessary – and it started with the dispossessed. Secondly, the so-called »Black Power Uprising« was an unparalleled testament to the power of music. The insurrection started in February, when a Carnival band depicted revolutionaries: Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and the Trinidadian Black Panther Stokely Carmichael. And the name of their performance? »The Truth about Africa«.

Inventing Modernity anew

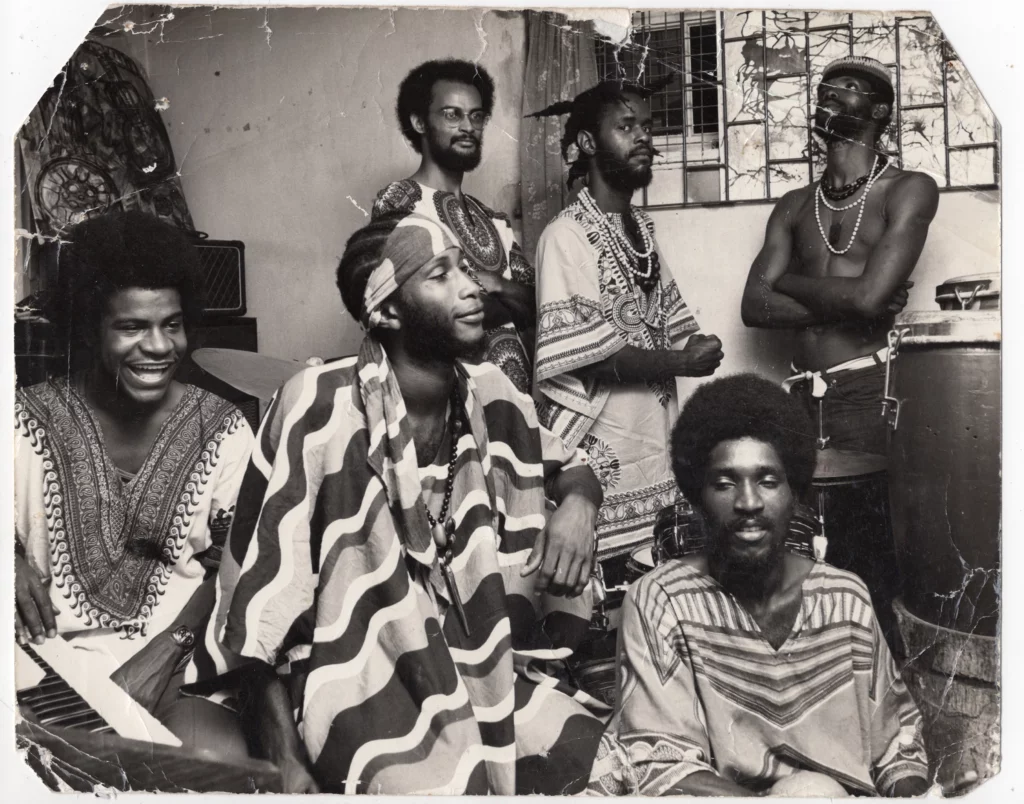

Imo must have observed these developments carefully. In 1972, he founded the Black Truth Rhythm Band. Its task: give the nascent political consciousness a musical-lyrical counterpart. Imo enmeshed himself in local, traditional styles like Calypso and attempted to temper their African heritage into a new form. By 1976, his efforts were shining in »Ifetoya«. It’s an experiment that, as Ben Lee remarked in his review, in retrospect, »fits perfectly within the more recognizable sounds of the 70s funk and afrobeat scene«. The decade had other ideas, though. Guitarist Andre Wallace once remarked that no label warmed up to the Black Truth Rhythm Band. »The promoter wanted us to change our clothing and our names. We were too Afrocentric for them.«

»The promoter wanted us to change our clothing and our names. We were too Afrocentric for them.«

Black Truth Rhythm Band

The band disbanded in 1978. Imo left Trinidad and Tobago. Today, he’s almost unknown is his country of birth. Yet, Imo was far more interested in Nigeria, the origin of the Calypso tradition. In the beginning of the 1980s, he met grandmaster Fela Kuti, became his tour manager and bassist, moved to Lagos. In Kuti’s Afrobeat Imo found a model for pan-African music – work with/off traditions to usher a new modernity. Whereas »Ifetoya« was variegated by the contrast of African and Caribbean elements, they merge on Imo’s first solo EP, »Oduduwa«.

Ein anderes System

It’s astounding how the revolutionary hopes of Imo’s music still make themselves felt today. Perhaps, because Imo has tasked himself with preserving them. By the 1990s, pan-Africanism had lost its glory. Yet, its afterglow still radiates from Imo’s Solo LPs – »The Glory of Om« (1995) und »Anoda Sistem« (2001) – warm like a sun. On the latter, the eponymous song »Another System« laments that African nations had just replaced strongmen by other strongmen so far. Only a united, inter-national Africa could enable real self-determination. Here, Africa is not a continent. It is a promise of freedom. Those that want to gauge its tectonic grandeur, will find a genius seismograph in Oluko Imo.