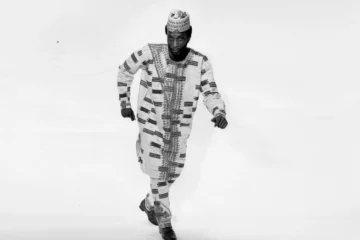

»OSometimes, the hardest social context brings out the best music,« says David Durbach aka DJ Okapi in conversation. With Afrosynth, he digs up South African music history. DJ Okapi, whose real name is David Durbach, has salvaged nearly 20 albums on his label since 2017. Most of the tracks date back to a time when so-called racial segregation still prevailed in Africa’s southernmost country. He talks about South Africa’s past and its sound: »bubblegum« music, a mixture of disco and soul that roared out of the speakers from Johannesburg to Cape Town in the 1980s.

You can hear the self-empowerment of the black population, which had been cut off from cultural life for decades, Lars Fleischmann wrote about the music genre. Bubblegum, however, was pejoratively referred to as such at the time, says David Durbach. »There was something escapist about the sound, some even claimed that it was superficial. People therefore believed that the songs did not address the political oppression. But the bubblegum musicians knew they had to be deceptive and use metaphors in order to speak up with seemingly innocent.«

The label as a reprocessing strategy

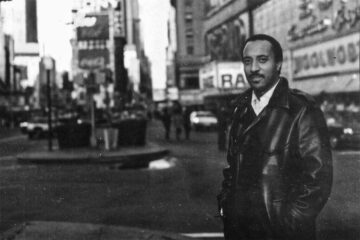

Durbach was born in Cape Town in 1983. When apartheid legislation disappeared from the constitution, he was attending primary school. In the late 2000s, he is drawn north to Johannesburg. »The city is at the center of South African culture«, says Durbach. »It’s the center of politics, it’s where life happens. Cape Town, on the other hand, has always been much more Eurocentric.« Also, the major recording studios and labels are in »Joburg«, as Durbach refers to the major South African city. If you wanted to learn about the music industry, you had to go there, he said. »And that’s what I wanted to do.«

In 2009, Durbach starts Afrosynth — as a blog to make information about albums of South African music history available. In 2015, he opened a record store, followed two years later by the label. Throughout this process, Durbach says he has always been interested in understanding his country’s history through music. »Afrosynth is my way of learning about myself as a white, male South African in this country. It makes me feel like I can play a role in preserving this country’s heritage. It’s a part of history that most people don’t care about anymore.«

33 secret release

Working on compilations for labels like Cultures of Soul and Rush Hour, Durbach gained his first experience in licensing old records. This, he says, led to contact with Maurice Horwitz, the owner of the renowned independent label Music Team. Howitz has known the South African music industry since the 1950s and has seen it all, Durbach says. »He was like a mentor to me because he gave me a sense of what the music industry was like during apartheid. He also has a huge catalog of music. I could license the first release of Afrosynth from him because of that.«

»Beginn dein Label nicht mit Katalognummer eins, sonst wissen alle, dass du gerade erst anfängst.«

Because of Maurice Horwitz, Durbach didn’t have to start from scratch for another reason. »To this day, I don’t know if he was pulling my le when he said, ›Don’t start your label with catalog number one, otherwise everyone will know you’re just getting started.‹« In fact, the first Afrosynth release is number 34. »Maurice said, ›three plus four is seven, and seven is a lucky number.‹ That may not have been serious advice, but I believed him at the time. Some people are still looking for 33 secret releases because of that.«

Now Dance

Durbach has recently returned to live in Cape Town—because of his young family and the circumstances in Johannesburg. Most days there is no electricity for half of the day, the city is poorly managed, and corruption and crime are on the rise, the DJ and label owner says. »No one is surprised when I tell them I’m coming back to Cape Town.« In addition, he says, his work with Afrosynth has now shifted much more to the Internet than during the label’s inception. »In the beginning, I was out in record stores a lot, digging around in archives and making contacts. I’ve made them, so I can continue to license music from Cape Town.«

In the future, Durbach wants to focus more on the sound of the South African 90s with Afrosynth. »I will try to show how house came to South Africa and how people translated the dance floor into their own context.« Kwaito is that dancefloor. The music emerged after the end of apartheid, when people drew new democratic optimism. As a result, the label is not only evolving in a new direction, Durbach says, »it will also tell another part of South Africa’s music history.«